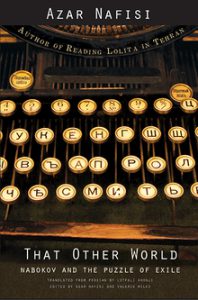

The foundational text for the acclaimed New York Times and international best seller Reading Lolita in Tehran

The foundational text for the acclaimed New York Times and international best seller Reading Lolita in Tehran

The ruler of a totalitarian state seeks validation from a former schoolmate, now the nation’s foremost thinker, in order to access a cultural cache alien to his regime. A literary critic provides commentary on an unfinished poem that both foretells the poet’s death and announces the critic’s secret identity as the king of a lost country. The greatest of Vladimir Nabokov’s enchanters—Humbert—is lost within the antithesis of a fairy story, in which Lolita does not hold the key to his past but rather imprisons him within the knowledge of his distance from that past.

In this precursor to her international best seller Reading Lolita in Tehran, Azar Nafisi deftly explores the worlds apparently lost to Nabokov’s characters, their portals of access to those worlds, and how other worlds hold a mirror to Nabokov’s experiences of physical, linguistic, and recollective exile. Written before Nafisi left the Islamic Republic of Iran, and now published in English for the first time and with a new introduction by the author, this book evokes the reader’s quintessential journey of discovery and reveals what caused Nabokov to distinctively shape and reshape that journey for the author.

Azar Nafisi has taught at the University of Tehran, the Free Islamic University, Allameh Tabatabi, and Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. She is the author of Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books, as well as Things I’ve Been Silent About: Memories of a Prodigal Daughter and The Republic of Imagination: America in Three Books.

Link here

s beguiling as that of Vladimir Nabokov’s to Véra Slonim. She shared his delight in life’s trifles and literature’s treasures, and he rated her as having the best and quickest sense of humor of any woman he had met. From their first encounter in 1923, Vladimir’s letters to Véra form a narrative arc that tells a half-century-long love story, one that is playful, romantic, pithy and memorable. At the same time, the letters tell us much about the man and the writer. We see the infectious fascination with which Vladimir observed everything—animals, people, speech, the landscapes and cityscapes he encountered—and learn of the poems, plays, stories, novels, memoirs, screenplays and translations on which he worked ceaselessly. This delicious volume contains twenty-one photographs, as well as facsimiles of the letters themselves and the puzzles and doodles Vladimir often sent to Véra. »

s beguiling as that of Vladimir Nabokov’s to Véra Slonim. She shared his delight in life’s trifles and literature’s treasures, and he rated her as having the best and quickest sense of humor of any woman he had met. From their first encounter in 1923, Vladimir’s letters to Véra form a narrative arc that tells a half-century-long love story, one that is playful, romantic, pithy and memorable. At the same time, the letters tell us much about the man and the writer. We see the infectious fascination with which Vladimir observed everything—animals, people, speech, the landscapes and cityscapes he encountered—and learn of the poems, plays, stories, novels, memoirs, screenplays and translations on which he worked ceaselessly. This delicious volume contains twenty-one photographs, as well as facsimiles of the letters themselves and the puzzles and doodles Vladimir often sent to Véra. »